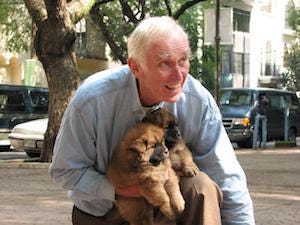

Studying Dogs - In Praise of Raymond Coppinger

I wouldn't call him a personal "hero" but this Behaviour Ecologist and Biologist had a profound effect on how I live and work with my dogs. He changed my perspective on dogs in very important ways.

Jean Donaldson taught me that dogs were not “furry little people” as depicted in many movies and TV shows. Karen Pryor taught me that there is a well established science of behaviour that can be used to help me teach my dogs effectively without conflict and confrontation. Patricia McConnell taught me that my own nature as a human being makes me fundamentally different from a dog and that I needed to acknowledge those differences in order to be a good caretaker and partner to my dogs. But it was Raymond Coppinger who taught me what a dog truly is and I will be eternally grateful for the wonderful legacy he has left behind.

I don’t remember how I first discovered the book “Dogs - A New Understanding Of Canine Origin, Behavior, and Evolution” by Raymond and Lorna Coppinger. I do remember that it was different to everything else I was reading at the time on modern positive dog training. There were no instructions on how to get my dog to “behave” better. No step-by-step guide to using a marker signal or how to deliver rewards in a timely manner. This was not a book about how to teach my dog, it was a book about the dogs themselves; their biology and their behaviour.

Not a dog training guru

Dr. Raymond Coppinger never presented himself as a dog guru in the mold of a Cesar Millan or Victoria Stillwell. His work was not focused on finding the most humane way to teach a dog or helping dog owners deal with their dog’s behaviour problems. He was not a professional dog trainer. He was a professor of biology and cognitive science at Hampshire College for more than 40 years with a focus on studying dogs. He described himself as a Behavioural Ecologist who specialized in the study of dogs in their natural environments.

I learned a great deal from reading Coppinger’s books. I learned that more than 70% of the dogs in the world do not live in a human households as pets. The vast majority of dogs are not selectively bred by humans. These dogs live in populations with no restrictions on their movement, reproduction, or behaviour except for those imposed by nature. Coppinger’s work of studying dogs in their natural environments included the garbage dumps and village streets around the world where free-ranging populations of “street dogs” flourish.

Growing up with dogs, I often heard dog lovers and especially dog trainers say that dogs were descended from wolves and that we should deal with their behaviour on that basis. But Coppinger pointed out a simple fact - our domestic dogs are not directly descended from wolves. They are the selectively bred descendants of the “street dogs” that Coppinger studied. If we are to learn anything about the nature and behaviour of our dogs from their lineage, surely we should look to the populations of free-ranging dogs that have existed for more than 15,000 years. And, while wolves do figure into the genetic lineage of dogs, they are far from their most recent ancestor.

Science above all

In the PBS documentary “Dogs That Changed The World”, Coppinger offers a theory of how dogs came to be domesticated. Dogs, he claims, evolved naturally from those wolves who had the greatest tolerance for being around humans. The experiments of Dmitri Balyaev and his foxes has proven that Coppinger’s explanation is not only possible but likely.

Much like the books by Pryor and Donaldson, Coppinger put evidence and provable science above all. Whether it was working with his sled dogs for more than 10 years, his Livestock Guarding Dog Project, or his later studies of “native” dog populations on five continents, Coppinger always put the science first. His dedication to gathering data and careful analysis of his findings produced a wealth of information that informs not just the academic community but dog lovers as well.

The Nature of Dogs

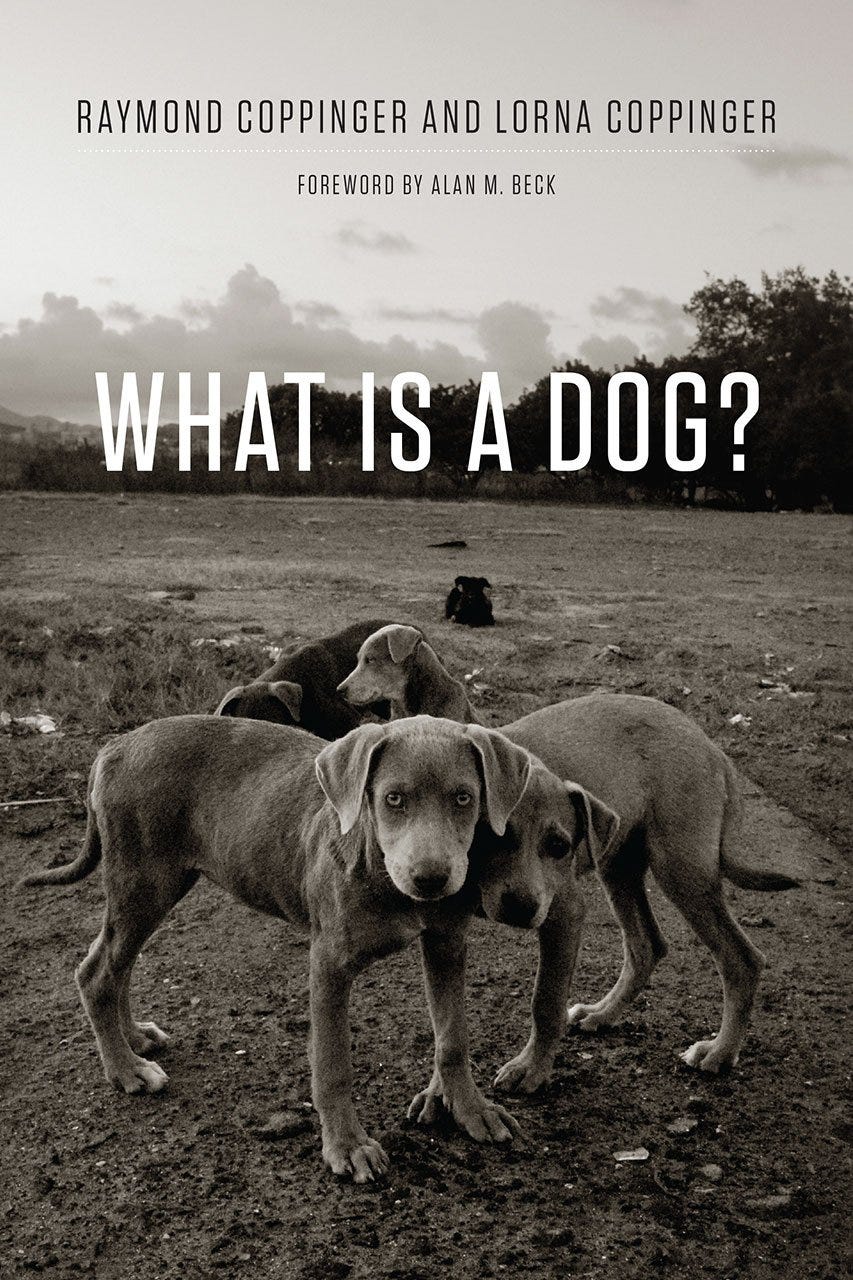

“What is a Dog?”, the Coppingers’ 2016 book is perhaps the most important book that I have read on dogs. While books on learning theory, behaviour science, and applied behavioural analysis helped me to understand the process of teaching my dogs, “What is a Dog?” helped me to understand the very nature of the dogs I was teaching. Specifically the chapter on Behavioural Ecology provided me with important insights into the behavioural tendencies, what you might call “instincts”, that nature has created in my dogs over literally thousands of generations.

The book describes Behavioural Ecologists as a sort of economist; they look at specific numbers and how those numbers relate to the survival of a population or species. In real terms, they look at an animals behaviour in terms of a cost/benefit analysis. What is the cost of a particular behaviour (often described in calories or energy used) versus the benefit of doing the behaviour? Over time, those behaviours that yield the greatest benefits for the energy it takes to do them will tend to become a part of the “nature” of the animal. Similarly, those behaviours that require a great cost for little or no benefit will tend to be avoided by default.

The dog in focus

Coppinger’s study of free-ranging dog populations provides the clearest picture of the nature of dogs. Essentially, from an ecological standpoint, dogs are vermin much like vultures, crows, rats, and other animals that survive off of the scraps and waste of human communities. We find them attractive and pleasant companions unlike other vermin species. Coppinger believes that this simple fact is a major contributing factor to the survival of dogs as a species. Looking at the Behavioural Ecology of free-ranging dogs brings the behaviour of our domesticated dogs into a much sharper focus.

For example, why are our dogs so easily trainable? Why do they seem to be so “loyal” and “do things to please us”? The Behavioural Ecologist would look at the cost/benefit analysis. It takes relatively little energy to do the physically simple things we ask of our dogs and the benefits are great - plenty of food, water, and safety from injury or harm. Our dogs are motivated to find ways to work for us because of what they get in return!

But this Behavioural Ecology also points out a very important thing that we may have gotten very wrong about dogs. The notion of “dominance” and “alpha dogs” falls apart under this kind of analysis. Simply put, the amount of energy a dog would need to expend to fight for their place at the top of some perceived hierarchy would not likely yield enough benefits to outweigh those costs. When we look at the behaviour of free-ranging dogs, we find relatively few acts of aggression except in cases where a dog’s very survival is at stake. Scarcity of food, threats from predators, or other life-threatening factors might cause dogs to fight among themselves.

Our domestic dogs rarely ever face anything approaching that kind of threat. In general, dogs would rather flee than fight. But it is our dogs who decide what is and is not valuable. They are the ones who who decide what is and is not worth fighting for. Behavioural Ecology simply provides us with a window into how these decisions are made from inherited genetic factors to the individual preferences of each dog. Behaviours like resource guarding and aggression are at least understandable from a Behaviour Ecology standpoint.

Seeing my dog more clearly

Coppinger’s analysis of the behaviour ecology of dogs has helped me see the behaviour of my own dogs much more clearly. The fact that they are adorable and make me laugh is just evidence of a successful scavenger species. Endear yourself to a human and get all the food you need! It explains why I can let my dogs run with other dogs, even dogs they have never met, and not worry about them getting into fights because they naturally try to avoid fights if possible. Understanding the needs of my dogs and how they might respond to a scarcity of those basics can help me understand their behaviour much more clearly.

Knowing how dogs evolved and what it takes for them to survive provides a basis for that understanding. Keeping in mind the simple formula of the Behaviour Ecologist has helped me to better manage my dogs. For example, common resources like food, water, toys, and affection are provided in plenty for our two dogs. There is no need to “contend” for these resources because there are enough to go around.

The behavioural ecology of dogs affects our training too. Understanding my dogs’ priorities allows me to select appropriate rewards when I want to teach new behaviours. It informs the way I go about my training so that I keep the costs low and the benefits high to get the best responses from my dog. It explains the variation in responses of my dogs in different environments where other priorities may interfere with what I want to teach them.

Biology and Ecology for Dog Owners

Science and data. These are not things most dog lovers think about when it comes to our cherished companions. But our dogs did not mystically pop into existence from a Disney movie. They have been around for at least 15,000 years and, like all animals, they have evolved with a certain set of tendencies and requirements. Having a more complete understanding of the biology and behavioural ecology of my dogs has made me a better trainer and steward for these wonderful animals. In large part, I have Raymond Coppinger to thank for that.

One very important thing about Raymond Coppinger is that he loved dogs. He loved them not just as subjects of his studies but as cherished companions and pets in his home. Through his remarkable career he studied working dogs and free-ranging dogs. He studied the biology and development of dogs from birth through adulthood. His contributions to the science of dogs have been matched by very few, in my opinion.

Sadly, Raymond Coppinger passed away on August 14, 2017. But the legacy he has left behind stands as a monument to a man who loved dogs so deeply that he made it his life’s work to truly understand them down to their basic nature. I will be forever grateful for his work and that he so readily shared what he found through publications and lectures that we can all still learn from today.

All that is left to say is - Thank you, Dr. Coppinger. Thank you.